This evocative illustration, from a manuscript of 1380 or so, probably done at a workshop in Northern Italy (which is much on my mind at the moment anyway, and more below) is, as you no doubt guessed, the 14th c. chivalric imagination of the seizure of Jesus by the authorities of Jerusalem in the Garden of Gethsemane. Notable moments (for Chivalric lay piety, at least) include Peter resisting, having thrown one of the Romans (or possibly Pharisees) to the ground, and the fact that all the soldiers are imagined as knights.

One day I’ll write that blog, about imagination and history and how we imagine the past, but for now, let’s just examine daggers. The man on the extreme left in a snazzy pink hat, has an ivory hilted dagger that occupies the space between a rondel and a baselard. The man on the extreme right has a baselard. And baselards were a particularly nasty form of fighting knife, often carried by German or Swiss soldiers, and featured in many period texts, from legal definitions to sermons against violence and luxury. In Piers Ploughman, ‘Sir John and Sir Geoffrey hath a girdle of silver, a baselard or a ballok knyf with buttons overgilt‘ by which we know these priests are too rich and probably too violent.

So naturally, I had to have one…

Sometime in 2013, when I first went to Verona, I spotted a fantastic baselard in the Castelvechio. As an aside, whomever decided to place an art museum in a fantastically complex late-fourteenth century fortress and palace earned my eternal approval…

Anyway, I found this amazing blade, which is supposed to have belonged to an English or German knight. What I loved about it was the strengthened backbone, which answered, for me, the question (from my martial arts/historical fighting life) as to whether a dagger could parry a long sword. The reenforced edge is down.

This, by the way, is a page from the Getty Mss of the ‘Fior di Battaglia, a late 14th or early 15th c. treatise of the chivalric fighting arts. This page shows the use of a heavy dagger to parry a sword. See why this is interesting?

Ms. Ludwig XV 13

At some point in 2013, I commissioned one of these from Leo Todeschini. I feel I must insert a warning here. If you like weapons, or fighting, or kitchens, or the material culture of the past, you will almost certainly spend money shortly after clicking that link. No. I mean it. You were warned.

No. Really.

OK. Let me admit to my addiction. If I could hook my royalty payments directly into Tod’s bank account…

Never mind. I asked Tod to build me the Verona baselard. In the original request, I planned to have the hilt made of ivory. Not elephant ivory. Goodness, I had the distinct honour of spending some time with the Kenya Wildlife Service and I have actually stood in the middle of a herd of 300+ elephants and watched them move and eat. I would be happy to use the dagger on the poachers, if requested.

But thanks to a fan, and now friend (this was and is one of the coolest parts of being an author of even a little fame) I received several pieces of 13000 year old (approx) mammoth ivory. This is not fossilized, BTW. It is simply incredibly old. It looks exactly like ivory, feels like ivory, etc. It has a few quirks. First, it stinks. No, really. I’m told that the amount of time it spent frozen in ice did not prevent some very slow decay. let me just say that I spent part of my misspent youth learning to do simple horn work with my mentor Erv Tschanz of Gen nis he yo Trading Post. Many is the morning I can remember drinking coffee that I had left next to a power tool and which had a fine layer of horn dust over everything….mmmm…

Ivory dust is a whole new level of horn dust…it’s finer, and it stinks more. Mammoths? wow. Even stinkier. Warning…wear a mask. And… don’t drink the cold coffee. Yes. Yes, I speak from experience.

Anyway… my eagerness to have the dagger trumped my ability to mail the mammoth ivory to the UK. Enough said.

Eventually, Tod made me this superb piece.

There it is, on my hip, hilted in a nice wood. Those two little tools sticking out are my eating kit…people did eat in the past, and that’s a knife and a pricker.

SO, all done, too bad about the smelly chunks of ivory in the basement.

Then, last year, on our fall hunt… that’s a deer hunt in 14th c. kit…

I fell heavily on it, slid down a rock, and cracked the hilt. I suspect every reenactor has a version of this story to tell.

After a lot of swearing, I decided, with advice from Leo Todeschini (warning!) to undertake the project myself. I would remove the existing hilt (I’d already gotten rid of a major piece sliding down a rock) and replace the brass rivets with silver and gold, while replacing the wooden slabs with mammoth ivory.

NB: I have some background in crafts. This was not my starter project.

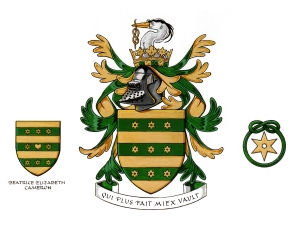

Leo told me how to get the slab handles off, and also how to take the furniture off the scabbard (another side note… I’m really quite a good leather worker, and the scabbard is the one thing I should probably have made myself, from scratch. But I didn’t… and I love Tod’s.) I had by this time decided to gild all the metal so that the knife and scabbard would be green and gold, like my coat of arms (see below). So, under Tod’s instruction, I took a chisel and popped the handles off and then drove the rivets back through the tang.

It was about this point that I had that sinking feeling that I was in over my head. I’ll talk about this more at the end, when I talk about crafting and risk, and how craftsmen think about projects. And maybe let Tod talk a little.

The next step was to cut up the ivory I had. Somewhere in there, I went online and priced my friends magnificent gift, because I already knew I didn’t quite have enough… or I had JUST enough. What I learned… was that I could not afford any more.

Period.

No pressure, but this set of Mammoth ivory scraps is what you get…

There followed an immense amount of reverse jigsaw-puzzle assembly. I would fit pieces, stare at them, and draw pencil lines.

At some point, looking online, I found this original baselard.

What mattered to me SO MUCH about this one (hilt looks to me like horn) was that each side was put on in three pieces. See the joins? That gave me a period dagger whose lines I could follow. I also liked the large rivets with designs. I went out and commissioned my friend Aurora Simmons to make me one, central rivet in gold.

Then I took my smallest scrap bits of ivory that I had been given and re-hilted the bye-knife and pricker set. It was good practice. All went well. No disasters. Sigh. Time for the big pieces.

Trembling in every limb, I cut my ivory. One chance, no take backs, and there was one little bit that looked like it was too small. Need to mention at this point that every piece I have (had) had a flat side and a wonky side. I did not want to mess about getting anything else flat, (go ahead, take some hand tools and make something flat. Call me when you get it flat. And those of you who CAN do this know why it’s no fun. Right?) so I went ahead with the ‘flat side down’ which still further limited my choices. I had five pieces. With something like brutal simplicity, I realized that I could cut one in half–split it, in fact…and have the right pieces.

I did that. It worked. In the process of using a jeweler’s saw to cut a largish piece of ivory in half very slowly, I learned several things.

1) 13K year old ivory has internal flaws and something very like rot. And all sorts of tiny imperfections. Surprise!

2) Ivory has a grain. I knew this, but when, in impatience, I switched from a light slow blade to a heavier more aggressive blade and then cut while talking to someone, I looked down to see my saw had deviated a full 1/8 inch…just wandered off on a grain line.

3) (all the news is not bad). Ivory is tough and forgiving, at least where it is not rotten. It has a REMARKABLE combination of hard/soft, elastic/rigid. I came to understand very quickly why craftspeople loved it.

So… I walked away, and wrote the first 100 pages of Red Knight IV, now called ‘Plague of Swords.’ I note that suddenly, lots of characters have things made of Umroth Ivory, which is the ivory of undead super-elephants. Wonder why…

Several days later, courage restored, I traced markings, boldly, on my pieces, and began to assemble what I call my slabs… the two sides, each of three pieces.

Close examination of this photo will show the hairline crack along the grain in the pommel (on the left). Not good. Remember, these pieces have a side and a direction. They only go one way… The hilt has real shape, and is narrower at the top and wider at the bottom, and so were my slabs. One way, and one way only…

It was about this time that I began to see, as I pressed forward, that almost every piece I had prepped also had a flaw. Thinning one of the cut slabs revealed a deep crack that ran right through the piece.

I didn’t have another piece. So…

I took ivory dust, mixed it with epoxy (really good epoxy, BTW) and filled the crack. It will be visible in the final. This is life.

That’s the ‘good side.’ It’s very pretty. Sadly, it’s the side that will face my hip when I wear it… yes, because now the curse of all the pieces that only go on ‘one way’ comes home to roost.

C’est la vie.

About this time, to raise my morale, Aurora arrived with my silver rod stock for rivets, my new flashy gold rivet, and my newly gilded scabbard furniture.

Emboldened, I moved on. I was, in fact, gaining confidence. A number of small but difficult sub-tasks went well. I re-drilled Tod’s rivet holes to 4mm. No problem. A little luck came my way…. Tod’s rivet holes are not perfectly centered. (NB, neither are the rivet holes on any medieval knife I’ve ever handled.)

See how off center those are? Here’s the luck part. I call this ‘craft luck.’ Tod’s slightly off center hole allowed me to drill without coming within 2mm of my crack. If I put the rivets through the area with the deep crack…

So… I glued the prepared slabs to the tang for cutting and drilling.

That, as you can see, went really, really well. I drilled very carefully, and I used three drill bits –the moment one felt dull, I switched. I managed to inflict ONE very minor chip in twenty holes. Also, my holes lined up.

Don’t laugh. If the holes don’t line up, you fake the rivets with glue, lie to to your friends, and cry.

Instead, empowered by success, I decided to take a risk I had,. until then, thought I’d skip.

Yes, I am a huge fan of authenticity. But, I fully confess, my concern for fracturing or splitting my 13K year old ivory was so great that I planned to tap my rivets through and polish them without peening. I planned, in other words, to fake them. I would use glue to hold the slabs to the tang.

But there and then, when the holes clearly lined up, I felt the music playing. And this is where I write about character, and about writing, and about craftsmanship. Because the music that plays for me when I take a craft risk is the same music that plays when I try something extraordinary in sparring, or other, more naturally adrenaline-filled parts of my current or past life.I asked Tod for his views on ‘craft risk’.

On the surface to others and even to myself, I am a very calm person who takes everything in his stride, but actually the subconscious tells a different story and in fact I know which the projects are that make me feel twitchy and those are the ones that are still hanging around after ages, because I keep finding reasons to not do it now. I have a complicated project… that should have been done and will tax me, but ultimately will be done and will be fine as experience has shown me that time and persistence and a wide skill set means you can pretty much make anything if you decide to, but still there is an unidentifiable niggle that holds me back. However what I have also found is that some jobs suit me and some do not and so looking at some work for example I know I cannot do that. Maybe because I don’t have the skill, but also because I don’t have the patience to learn the skill. The other aspect is just be brave; try it and if you can’t, then find someone to extricate from your hole and get them to sort it. I put sculpting into this category, I try and if I fail then I have a friend who can.

CGC note Yep. If I dick it up, I call Aurora.

Is it all old hat? Well mostly yes, but still things have challenges, but mostly now they come down to making a job you know should be faster, faster. Money is what drives a commercial craftsman now, as it was back in the day. Yes I do it for love of the craft, learning, developing and all manner of reasons, and indeed pride.

The next quote from Tod I include on behalf of all high-level craftspeople everywhere.

Sorry to keep coming back to money, but that is the venal nature of work, but is it risky? Yes if you have a bill to pay tomorrow and that dagger has to right for a customer, but generally if a piece goes wrong, it rarely is completely buggered and so it still has value and usually is completely salvageable, but may not be what it was meant to be, so if you can wait to sell it until next month or next year then you still get your money and you just start again. As I said before, the real risk is usually in that quotes go wrong. If I am really uncertain of a piece I will tell the customer of my worries or suggest another maker that I know can do the job; that said I do tend to get many of the tricky jobs out there. In my situation, if I think a project is truly beyond me I will turn it down, but actually I can’t think of when I last turned a job down for that reason, the real risk is simply in not making money on it, or not doing the piece justice.

CGC note — I make stuff for fun, and to learn more about the past. But the single most common complaint that I hear from craftspeople after ‘he never paid me’ is about customers who do not understand the risk factor in estimation and production, in time and in skill. We have a joke in reenacting. It has many variations, but here’s my favorite:

This weekend in my spare time, I will attempt to recreate an object in a matter of hours that took three different professionals from three different guilds forty hours to make. Yes, this is my first time working (insert material). No, I don’t have any extra. Yes, it cost hundreds of dollars just for the raw materials.

For professionals like Tod, like Aurora, like Jeff or Jiri or Craig Sitch, they have a much wider and deeper range of base skills than most of us… but they still don’t know all the skills. The dagger I’m recreating would have involved:

A tanner

a leather dyer

an ivory worker

a blade smith

a white smith (finishing and polishing the steel blade)

a goldsmith (gold and silver and possible even the riveting itself)

a leather worker (to make up the scabbard)

Right. Have I raised the tension? Back to the baselard…

I drove the rivets. What the heck. I like to do things right, and my feeling… an odd word, but an accurate one…was that all my holes went through ‘healthy’ ivory and that ivory was actually as forgiving or more forgiving than wood.

Every rivet had its own burst of anxiety and adrenaline. For each one, I measured a length of 4mm silver rod, cut it with the heavy sheers you can see int he top right, and then drove it with careful; taps into the prepared hole. Then, with the riveting hammer (my grandfathers, BTW) I worked the protruding bit of metal until it swelled, then turned the hilt over and did the same on the other side. Rivet by rivet. I did the ones in the thinnest and worst bits of ivory first, down by the blade. Then at the pommel. No cracks.

So I did the rest.

Damn. No cracks.

Which is to say, there’s still a large crack from phase III, and it will always be there. But I didn’t inflict it. It’s the result of 13K years in the ice of the Canadian north.

There’s the back of the finished product.

And there is the front. See the crack? It is not perfect.

I’m afraid I love it anyway. But I don’t have a customer waiting to tell me that he wants one without a crack.

BTW, see the gold rivet? That’s my badge, or what the Japanese would call a mon. Far right, below.

So… what did I learn?

First, I learned twenty things for my current novel. Umroth ivory, and ivory dust, now permeate the book. The Umroth themselves, and their master… whoops! spoiler…

But mostly I was reminded that craftspeople are risk takers, not stolid, dull people with limited skills. In fact, most really good craftspeople can probably make just about anything, because what you eventually learn, as I think Tod was saying, is that you can make anything. You can learn to learn. You can pick up a new skill. This takes a special kind of mind, and a special kind of daring. As a sword teacher, I know that the first step to learning a martial art is to admit you know nothing and learn. This is harder for some than others. The same applies to making things.

I think I find craftspeople fascinating for dozens of reasons…my grandfather was one of them, and I worshiped him; I grew up making stuff with him and with my dad, who’s no slouch. But more, as I grew to know them as a ‘breed,’ I realized what complex, brave people they are; how confident they have to be in themselves to face the reality of concrete success or failure every day. You can tell yourself a poem is good. You can’t hide the crack in the ivory.

And… my mages, in fantasy, are craftspeople. They make things. They assemble power carefully, they work with tools like ritual and memory palaces, and they need craft luck and brilliance and massive self-confidence to impose their wills on reality.

Like craftspeople do, every day. The real magic.

Oh, yes, I learned one more thing, from my wife, Sarah.

The finished knife still stank of 13K year old dead mastodon. But a little wintergreen oil, and it’s the best smelling dagger in my kit.

So much to learn.

To me, the crack gives it increased ‘authenticity’. So often in museums, when you see items that were used [as opposed to items that saw little or no use in their functional lifetimes] they are filled with hints of the drama they endured during use. I recall seeing a set of gold sword fittings from a Vendel Era hilt in the Historiska Museet in Stockholm, on one side of the crosspiece there was a nick, precisely like you would get from light contact with an edged weapon. O have replica weapons in my collection that sport nearly identical marks. That nick spoke volumes about the life of that sword, and forever put to rest the argument that these weapons, and the fine gilt helmets of the same time, were not fought with.

Reblogged this on parmenionbooks and commented:

time to learn something new…..

Thanks as always.

As someone who has made things for myself and occasionally others, as well as having grown up with dad, making things and many of his friends being fine craftsmen. I have experienced the doubt of making the cut, but as with most things, when one allows the possibility of “failure”.. with adequate preparation one gain freedom.

And paraphrasing Musashi, as one “masters” one area, one is more able to start “mastering” others.

The lack of making things in most peoples lives is a shame, we as a species are where were are, because we are all movers and makers, unfortunately not many of us these days, to do either very much or very well

-“As a sword teacher, I know that the first step to learning a martial art is to admit you know nothing and learn. This is harder for some than others. ”

This for me is the biggest hurdle to learning and guiding others to acquire new skills.. In my day job I get to work with a few hundreds of new people every year to handle their bodies and weapons. Yet despite coming to a place to “learn” too often, one encounters those that are convinced they know better than you how to get them to acquire the new skill you are giving them, despite the obvious flaw, that if their way was so good… why cant they then already do it! then the others who have convinced themselves that they will never be able to acquire the skill because they are hopeless.

I am sure that a large of this in innate to humans, but it is worsened IMO by our culture and “educational” systems, that further embed these notions, which as I read recently, it stops us from accessing our true power…

Me rather thinking through the keyboard…

Thanks again

I always enjoy your comments. I’m starting to look forward to them… 🙂

Oh now… you’ll make me blush! 😉 I look forward to your posts as they are not only interesting and informative but also provoke thought and communication, so I look forward to writing a comment!

Great post! There is nothing quite like the feeling of satisfaction of having created something pleasing (and maybe even useful!) with your own hands, skills, patience and risk-taking. What I want to know is, where the hell did you friend get 13,000 year old ivory from?!

Thanks for your description of ivoryworking. Working bone has always sounded nasty.

You know, I am not so sure of the station and fighting role to the soldiers in that missal (whose title tells another story about princely and clerical excess). Scudieri with harness of greaves and cuisses appear in Lippo Vanni’s Battle of Sinalunga and probably Leonardo’s Life of St. James in Pistoia.

This article has inspired me to try to make a baselard. It won’t be as nice as yours, but it will be functional, and heavy duty. Oh, and it won’t be very authentic. I’ll be using a grinder.

Now if I could just write like you, with a degree of the knowledge and authenticity you bring to the table. Been a huge fan of yours since “Killer of Men”. Now if Barnes and Noble would carry your stuff.

Thanks Denny. Good luck with the Baselard!

There is a satire on baselards in this middle english poem. You will have to load up the book in google play. They digitized it.

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=s9iobZUO8nUC&rdid=book-s9iobZUO8nUC&rdot=1